Transactional Analysis

Transactional Analysis (TA) is a method for analysing and understanding our behaviour and our interactions with each other. It is a simple method, easy to understand and apply to the many scenarios we encounter each day and in all areas of our lives. As a result of our understanding, we become aware of and are able to change our behaviour, and positively influence our personal growth. TA demonstrates great versatility, covering a wide variety of areas. The fundamentals – Ego States & Transaction Types – are shown below. Other areas are listed here, with each subject linked to a corresponding blog post:

My blog also contains a wealth of additional TA information which can be accessed via the relevant categories in the archives (Ego, States, Time Structuring, Strokes, etc.) Examples include Internal Dialogues, We Change Anyway, and Are You Still Breathing?

The blog is also where you can find a comprehensive, step-by-step summary of the self-development process: The List.

Ego States

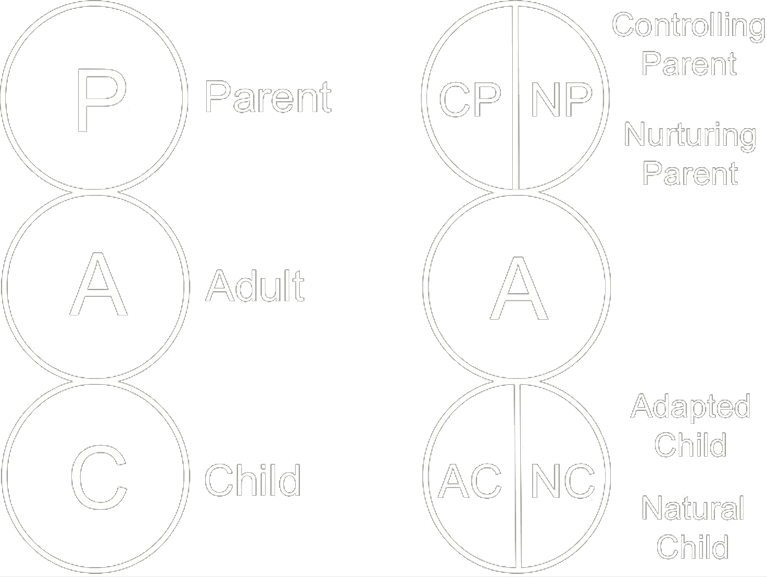

Every one of us displays behaviour which falls into one of three categories. Those categories are called ego states. In the simple diagram on the left the basic ego states are shown. The diagram on the right represents the Parent and Child ego states in more detail.

These states develop during the early years of our life and are influenced by those who are involved in our upbringing – usually our parents – and our responses to what happens to us. It is important to say at this stage that all three are required for a healthy existence and quality of life. In addition, each ego state has positive and negative aspects, which are described below.

Parent Ego State

The Parent ego state is created by the messages we receive from our parents. This means it is different for every one of us. My parents were different to yours and so the messages I received when I was growing up are different to the ones you received. A small child often has nothing else to do but take in the world around it. It tries to make sense of what is going on because every piece of information, every clue to appropriate behaviour can help with its survival. So, the child takes in huge amounts of information from its surroundings, in particular from its parents. This information is internalised in the Parent ego state. It is divided into two parts:

Controlling Parent

This is the parent who tells us what to do. At its best, it provides us with vital advice and guidance on how to live our lives (+ve CP). At worst it manifests in stifling, critical behaviour (-ve CP)

Nurturing Parent

This is the parent who cares for us. When done properly we feel cherished and supported (+ve NP), but too much and we are smothered and not allowed to discover for ourselves (-ve NP).

Adult Ego State

It is the Adult ego state which allows us to interact with others without playing games. When we are in Adult we work without emotion to gather information, process it and act accordingly. A strong Adult ago state orchestrates the other ego states in a way which limits their negative effects, and makes use of the positive ones. It is this ego state we must seek out when we find ourselves in a (psychological) game. This means that when I am in an argument and reacting from the Child ego state (emotional), I must find a way to communicate from the Adult ego state (see Transaction Types, below).

There is additional information on ego states here.

Child Ego State

Our Child ego state represents how we felt as a child when growing up. It represents our joy and our creativity, but also our worries and fears. Again, it is divided into two distinct parts:

Adapted Child

This is the child that responds to the rules set out by our parents. Depending on the choice the child makes, it will either play by the rules or rebel. When a mother tells her son to sit up straight at the table, the child may do so because he knows his mother will be pleased with him. He will receive strokes (attention) for his behaviour. Maybe, after a week of doing so his mother no longer notices and so in order to regain her attention, the child begins to slouch until his mother reminds him of the right way to sit (doing so, perhaps, using negative strokes.)

Natural Child

This refers to the way we behave when we are free and unrestricted by any rules. It allows us to be creative, joyous and carefree. However, if behaviour oversteps social boundaries it could cause embarrassment or offence.

Transaction Types

When we interact with each other, there are three types of transactions:

- Parallel (Complementary)

- Crossed

- Hidden (Ulterior)

1 – Parallel (Complementary)

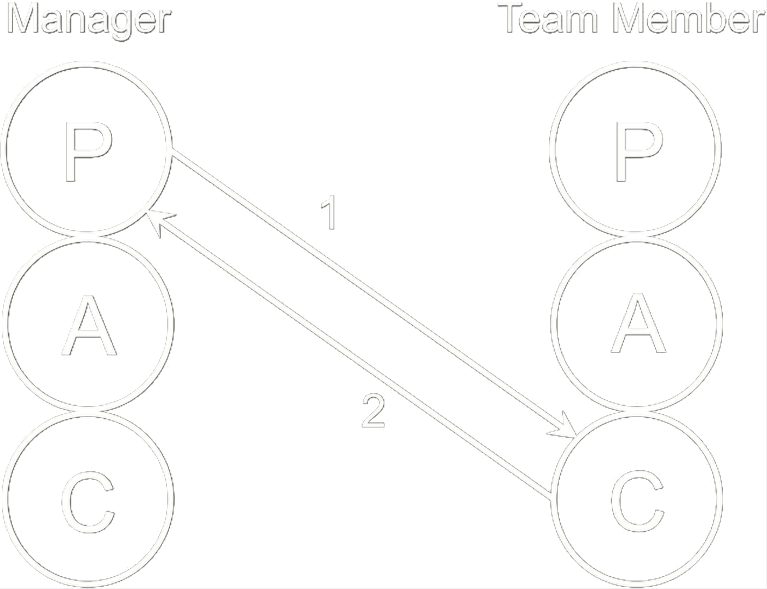

Parallel or complementary transactions are those where the individuals respond as expected. This means when I address someone’s Child ego state from my Parent ego state, I expect them to respond from their Child. I can do this with a nurturing intention to help or support (+ve NP), but at the risk of dampening their own initiative or abilities (-ve NP). Or I can do this from a controlling perspective by providing guidance, direction and useful advice (+ve CP), or alternatively by criticising them and being negative (-ve CP).

In such cases – when the players ‘know’ which roles to play – the interaction can continue through numerous transactions, each person reacting as expected from their set ego state (see the diagram below). In this example, the manager is in the role of negative Controlling Parent. The initial interaction causes the Team Member to inhabit the Adapted Child creating an emotional response which only serves to exacerbate the Manager’s mood. (The numbers in the brackets correspond to the arrows in the diagram.)

Manager (1): You still haven’t given me the report I asked you for. You are always doing this!

Team Member (2): It wasn’t my fault.

Manager (1): It’s never your fault. So, who’s to blame this time?

Team Member (2): I wasn’t given the data by accounts.

Manager (1): Why didn’t you inform me of this earlier?

Team Member (2): You were busy. I didn’t want to disturb you.

Manager (1): Just because my door is shut, doesn’t mean you can’t come in…

Team Member (2): Yes, but… you see… I… sometimes people say one thing and mean another… it can be difficult to… I’m sorry…

And so on, until:

a) Someone breaks the cycle by coming from a different ego state.

b) The manager feels he has made his point (or the Team Member ‘gives up’).

c) One or both parties have received the strokes (attention) they need.

2 – Crossed

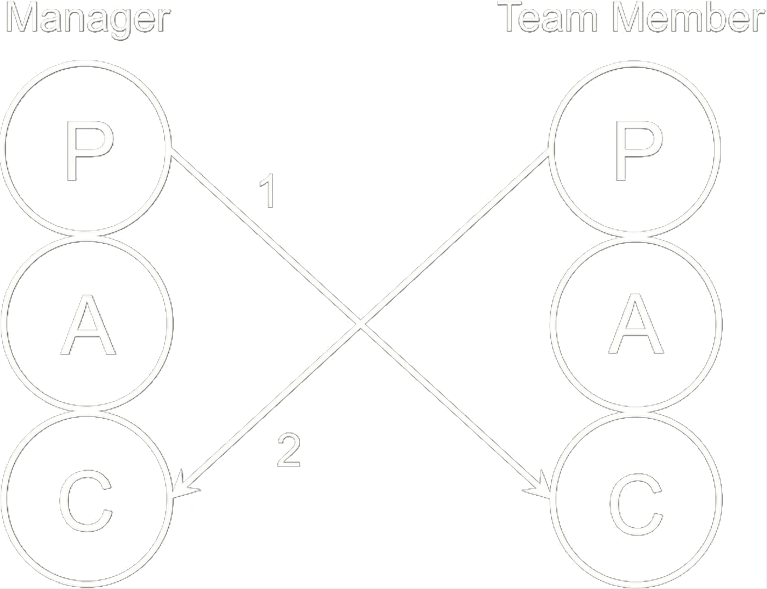

These are transactions in which the respondent comes from an ego state which is not the one ‘expected’ by the initiator. Because of this, crossed transactions tend to come to an end sooner than parallel transactions. The first diagram below shows the interaction with the respondent in (Controlling) Parent ego state, whereas the second diagram shows an Adult response to the same initial transaction.

Manager (1): You still haven’t given me the report I asked you for. You are always doing this!

Team Member (2): And you are always picking on me. If you were as critical of the accounts department as you are of me then maybe I would get the information I asked them for.

Notice how different this response is to the first example (Child Ego State). It feels like a different person, but in reality we all possess so many different ways of reacting to the world around us. What’s important to remember is that we always have a choice.

Manager (1): You still haven’t given me the report I asked you for. You are always doing this!

Team Member (2): Yes. I understand the problem and I would appreciate your help in getting the last information I need from the accounts department.

Again, this is an example of a different choice. It takes awareness and the creation of a gap between trigger and response to be able to react in the most appropriate way possible. It takes practice, of course. But once you begin to see things more clearly, you will automatically have greater control over the only thing which you can definitely influence in such interactions: yourself

Just by reading the different responses from the team member in each of the three examples above, we can actually feel the difference between the contrasting scenarios. We can feel the childish response in the first example, and its easy to see why that would tend to perpetuate an unhelpful dialogue. In the second example, both manager and team member are behaving from their Controlling Parent ego state. Again, unhelpful. It is only when the team member deals with situation from the Adult ego state that we feel the situation is being diffused and a solution to the problem is in sight. Of course, this is something a good manager would do in the first place.

3 – Hidden (Ulterior)

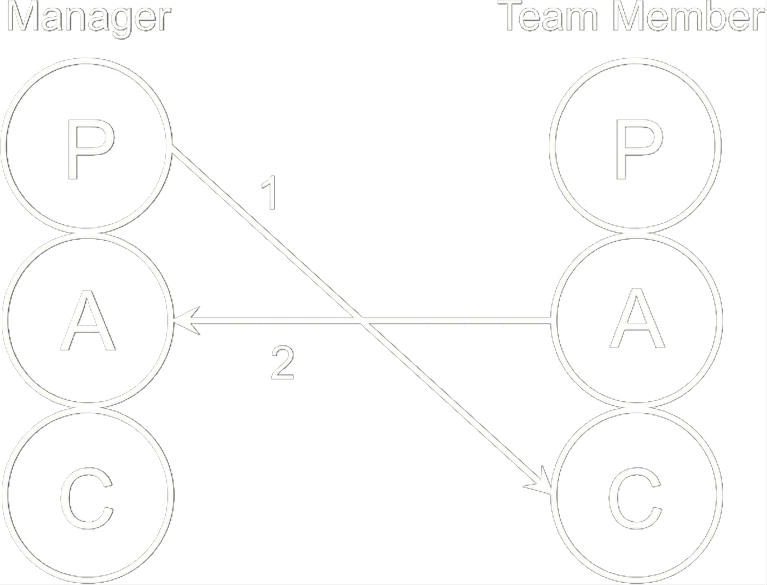

Hidden transactions are the ones which appear to be straightforward communications but which actually contain an unspoken message that carries with it a hidden agenda. It is these transactions which mostly lead to games being played. They can often be seen in personal relationships and avoiding them can require some discipline from the individuals involved. With ulterior transactions there is a hidden hook which pulls us into a game if we are not aware of what is happening.

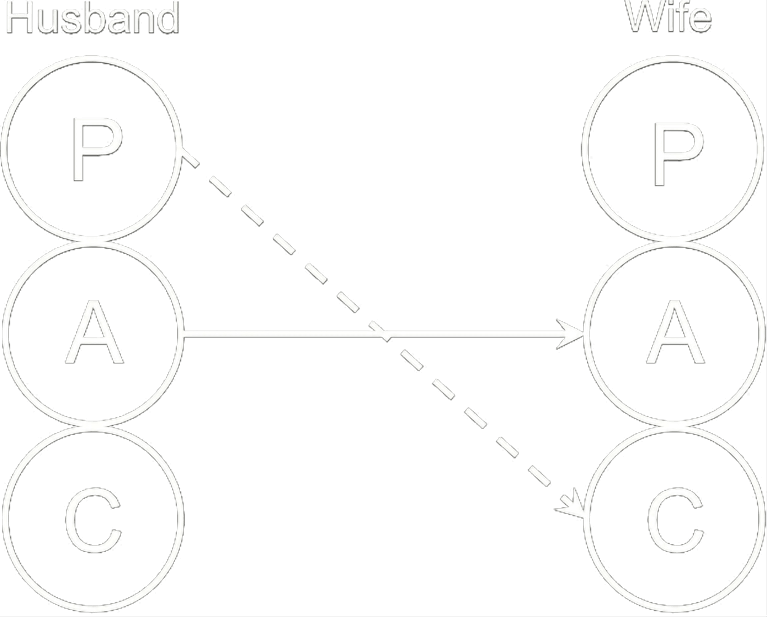

In the example below we shall consider a husband and wife who have been together for a number of years. For some time it has bothered the husband that his wife can sometimes be forgetful or misplace things. Having used the car the previous night she left the keys on the kitchen table rather than return them to the shelf by the front door where they ‘belong’.

Husband: Have you seen the car keys?

This in itself is an innocent question. A request for information which is represented by the line from Adult–Adult. However, there is an underlying message shown by the dotted line which indicates a Parent-Child transaction and can be formulated thus:

Husband: You had the keys last and they are not where they should be!

This comment is more inflammatory and, because we know there is an issue between the husband and wife, it is safe to assume that it’s an accusation (made from negative Controlling Parent) to the wife for being unreliable with the car keys.

How the wife reacts depends on her mood, her awareness of what is happening and her willingness to play the game. Here are some of the options:

- Wife: Yes, they are where I left them last night. I told you where they were when I got in last night, but you didn’t listen. (Parent)

- Wife: Will you leave me alone? I didn’t do it on purpose, you know. (Child)

- Wife: (Oh, you know what I’m like.) I left them on the kitchen table. (Adult)

Option 2 is the one most likely to prolong the interaction and, as soon as this happens, the subject of the interaction is no longer the location of the keys, but the failings of the other person. The husband and wife are in a game and the longer the game goes on the greater the pay–off for both people.

For example, the wife can end up screaming at her husband to leave her alone whilst at the same time feeling useless because she ‘misplaced’ the keys; and the result for the husband may be a wielding of his perceived superiority over his wife followed by her walking out on him.

One of the goals of games is to receive attention (so-called strokes). So if each individual can receive positive strokes and do so without being manipulative, they are much less likely to resort to such behaviour. Option 3 diffuses the situation and hints at the need for acceptance on the part of the husband – there is also a parental element which suggests, “I know what you’re trying to do and I won’t play your game.” Other reasons for playing games are to reinforce our opinions (of self, others, or the world) or to perpetuate our Script.